Putin’s New Neighbor

How an unknown female horse rider acquired Putin's Neighbor property for 18,000 times below market value

Maria Klementieva won the Russian championship title in 2021. Photo: fksr.org

How an unknown female horse rider acquired Putin's Neighbor property for 18,000 times below market value

Maria Klementieva won the Russian championship title in 2021. Photo: fksr.org

A year-long Explainer investigation reveals how Maria Klementieva — a little-known Russian dressage rider and Cyprus passport holder — became the registered owner of a Rublyovka estate just a few hundred meters from President Vladimir Putin’s Novo-Ogaryovo residence after a 2022 transfer that recorded a sale price of only 500,000 rubles (about €5,400). Drawing on property records, offshore filings, corporate accounts and aviation logs, the investigation traces a web of Cyprus and BVI vehicles, intercompany loans, debt write-offs and “golden passport” structures linking Klementieva to Russia’s state-contract elite and to jets associated with the Rotenberg network.

The transfer moved roughly 9,7 billion rubles (about €98 million) of prime real estate from a Cyprus nominee company into the hands of a single private individual, on paper, at a fraction of market value and at 0.07% of cadastral value. It took place in September 2022, in the middle of the war and sanctions, and inside a specially protected zone controlled by the Federal Protective Service (FSO) around Russia’s most sensitive presidential residence. (i)

This report reconstructs the transactions, timelines and networks behind that disposal — from offshore loans and same-day debt write-offs to the liquidation of the Cyprus vehicle — and shows how a previously obscure sportswoman with a Cyprus “golden passport,” ties to the Transmashholding ecosystem and control of a medieval château in France became, on paper, one of the closest landowners to Putin.

The winner of the 2020 Russian Dressage Cup spoke about her partner, his strengths and her immediate plans.

The Athlete: From Obscurity to Putin's Neighborhood

Maria Klementieva, now 43, is the woman now registered as owner of the Zhukovka estate. She did not return to international sport in 2024 merely to compete. She sidestepped the International Federation for Equestrian Sports' (FEI) neutrality requirement for Russian athletes by competing under Cyprus's flag instead of signing the pledge to renounce support for Russia's war.

By 2021, Klementieva had built a reputation as a promising dressage rider, winning first place and Russia's national title in freestyle dressage—a discipline where horses perform specialized movements including piaffe (trotting in place), trot, and canter choreographed to music. She spent summers in Europe, primarily France, nearly qualified for the Tokyo Olympics before her horse sustained a hoof injury, and set her sights on Paris 2024.

Yet the same rider acquired a dacha (country estate) just 500 meters from Putin's residence—part of a cluster of assets that shifted to a single owner on paper for a fraction of their market value.

In 2015, Klementieva obtained Cypriot citizenship through the investment program requiring at least €2 million (approximately $2.2 million). The Cyprus Papers—a major data leak exposing golden passport schemes—reveal an omitted detail: her "husband" also received a passport, possible only with an official marriage certificate as part of a family package.

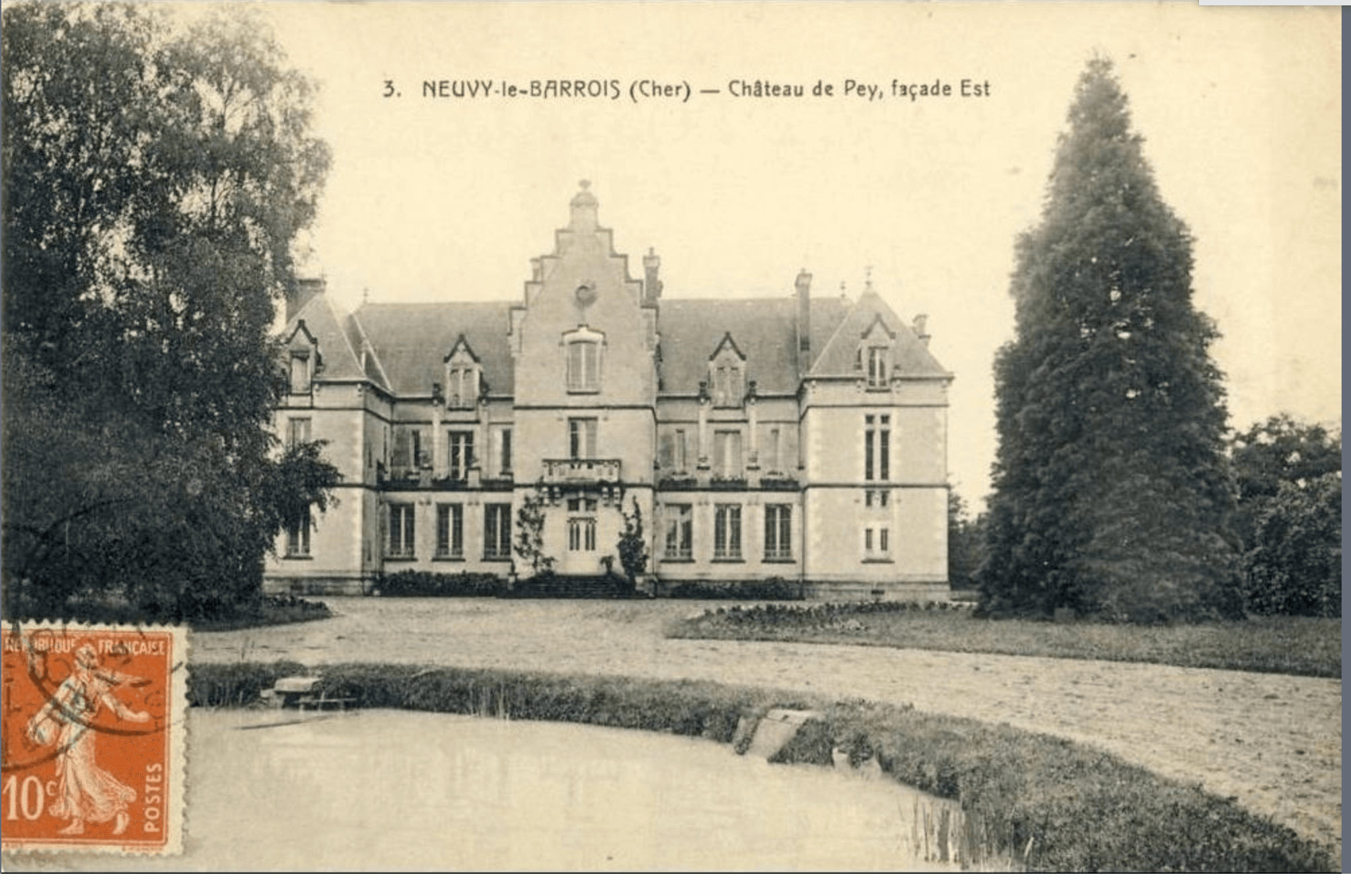

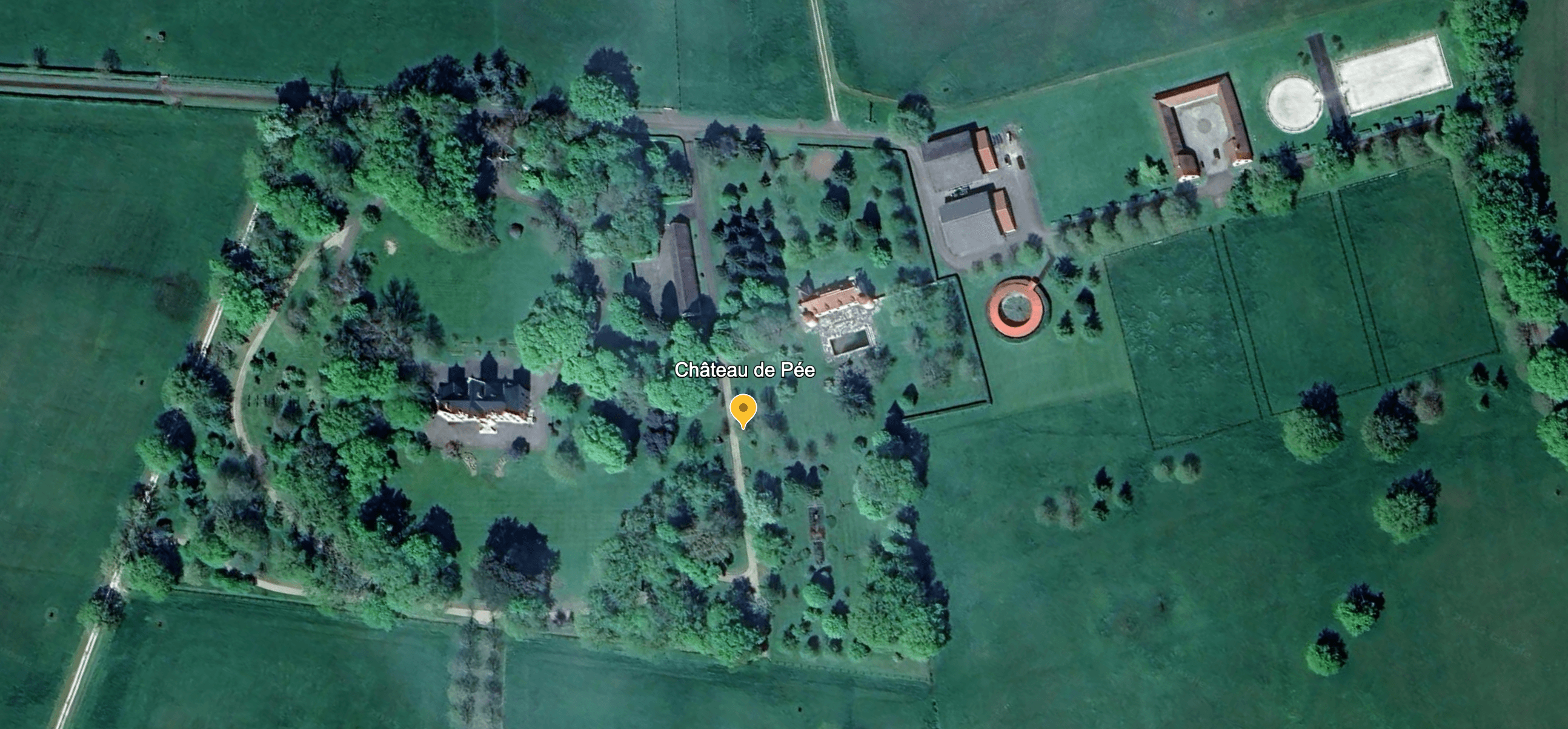

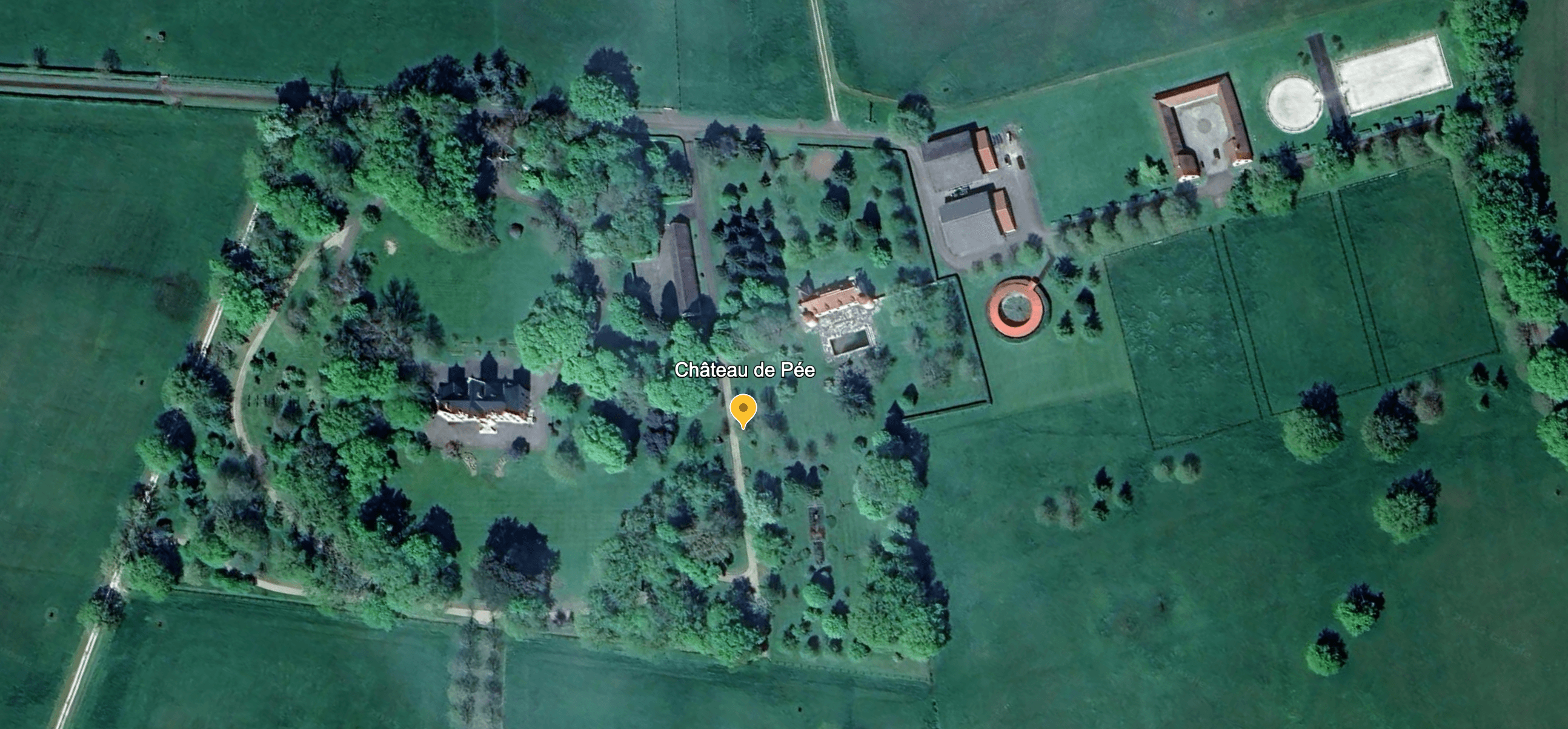

French corporate records reveal another dimension of Klementieva's holdings: she manages the medieval Château de Pée, an asset she took control of in 2017—earlier than obtaining her Russian Master of Sport title. Located in the commune of Neuvy-le-Barrois, approximately 230 kilometers (143 miles) south of Paris in the Cher department, the château comprises 45 hectares (111 acres) of land.

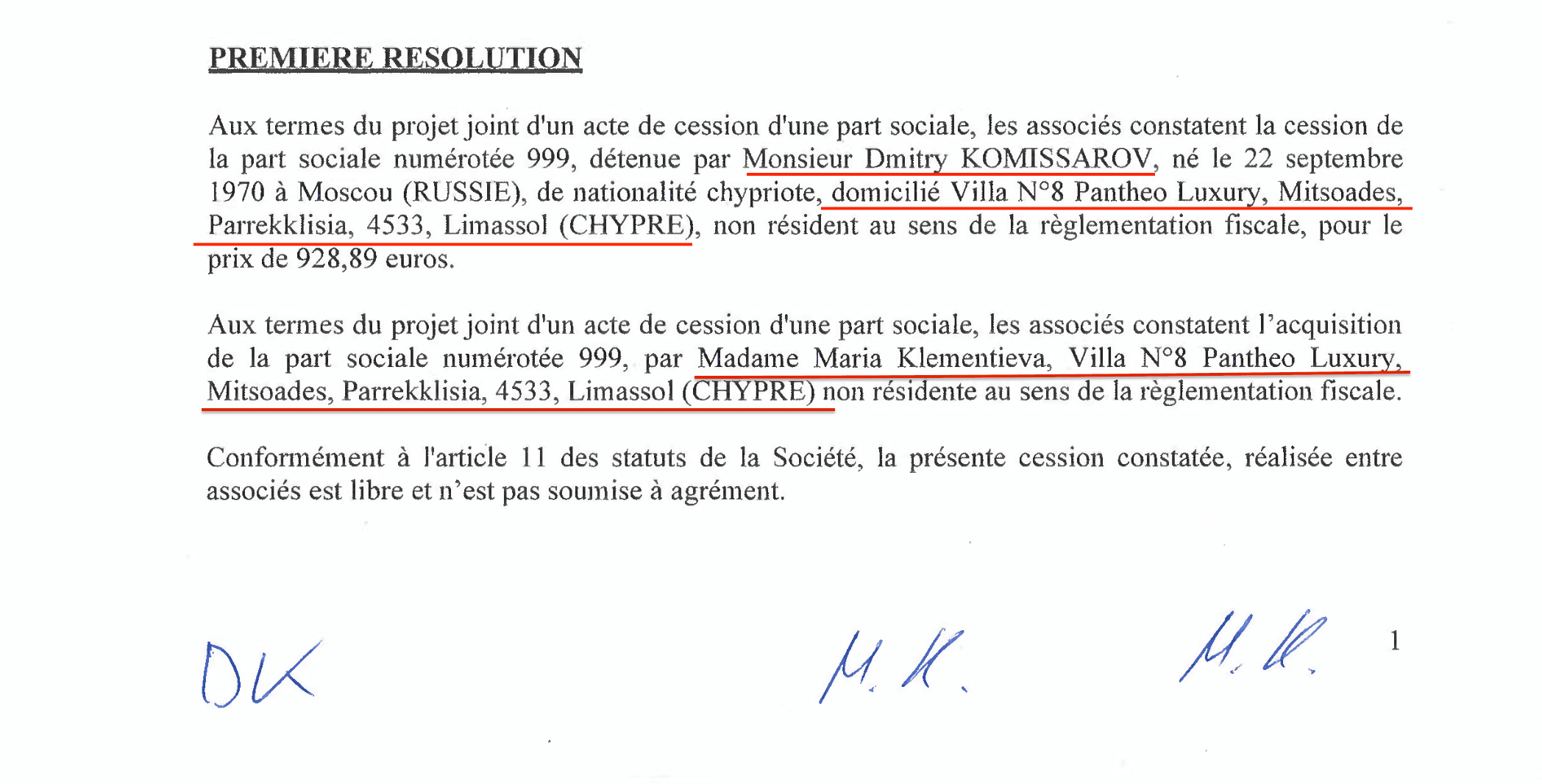

In 1987, French attorney Patrice Gassenbach purchased the estate and placed it in a company to minimize taxes. Thirty years later, control moved to a Monaco firm—a jurisdiction where beneficial owners are shielded from public disclosure. In November 2017, two new shareholders joined the French company: Maria Klementieva and Dmitry Komissarov, both Russians with Cypriot passports, both listing the same Cyprus address at a villa in Limassol.

An estate just hundreds of meters from the president's residence on Novo-Ogaryovo Street was acquired for a pittance during wartime by the striking, unmarried athlete Maria Klementieva. Her name remains unknown to the Russian general public, and her biography contains significant gaps.

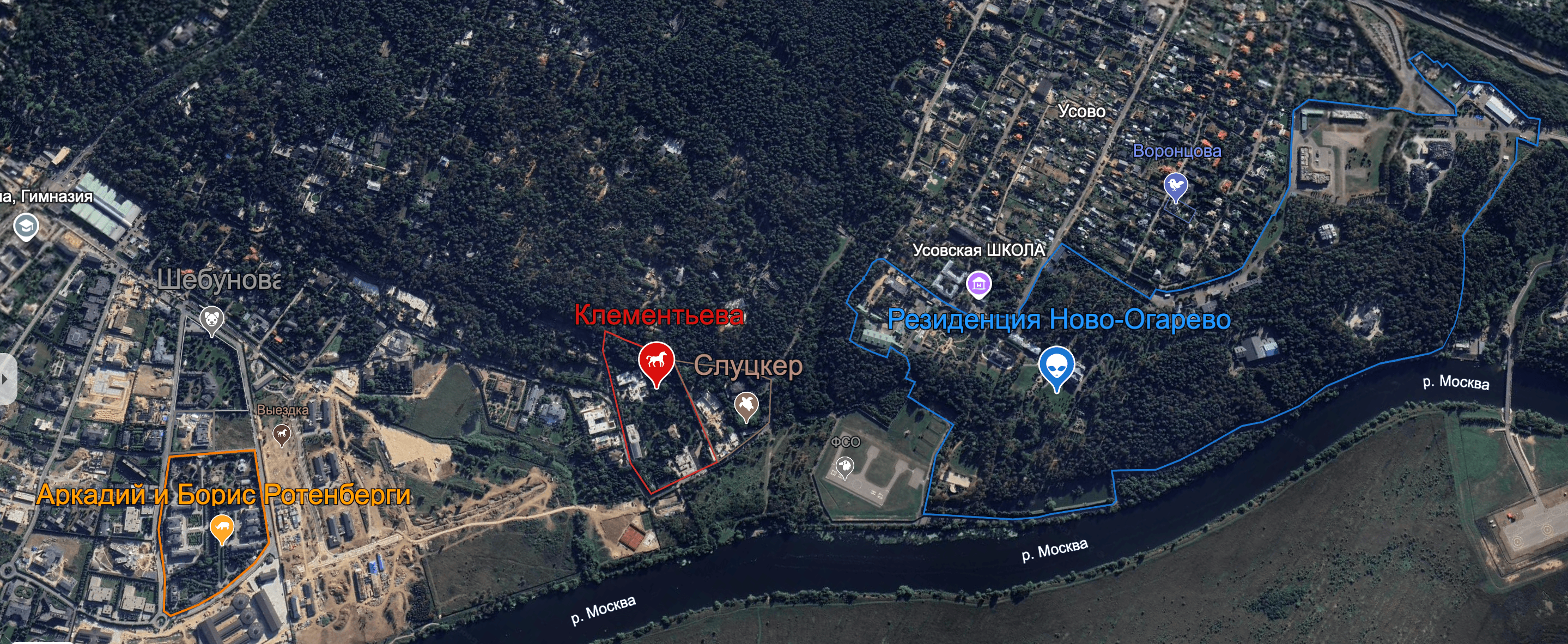

Most significantly: in the midst of war, she became Putin's neighbor. Only a small stretch of forest separates their properties. She acquired a plot in a specially protected zone entirely controlled by Russia's Federal Protective Service (FSO)—essentially the presidential security apparatus—for 500,000 rubles (roughly the price of a used Lada automobile).

Her estate now sits alongside villas belonging to the Rotenberg brothers, Olga Slutsker (also a Putin neighbor), Elena Shebutnova (alleged partner of Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu), and other members of the upper class. She is closer to Putin than anyone except Slutsker.

A holy place — for 0.07% of cadastral value

From September 7 to October 25, 2022, six real‑estate assets with a total market value, at current prices, of about 9 billion rubles ($90 million) transferred to Maria Klementieva. (i)

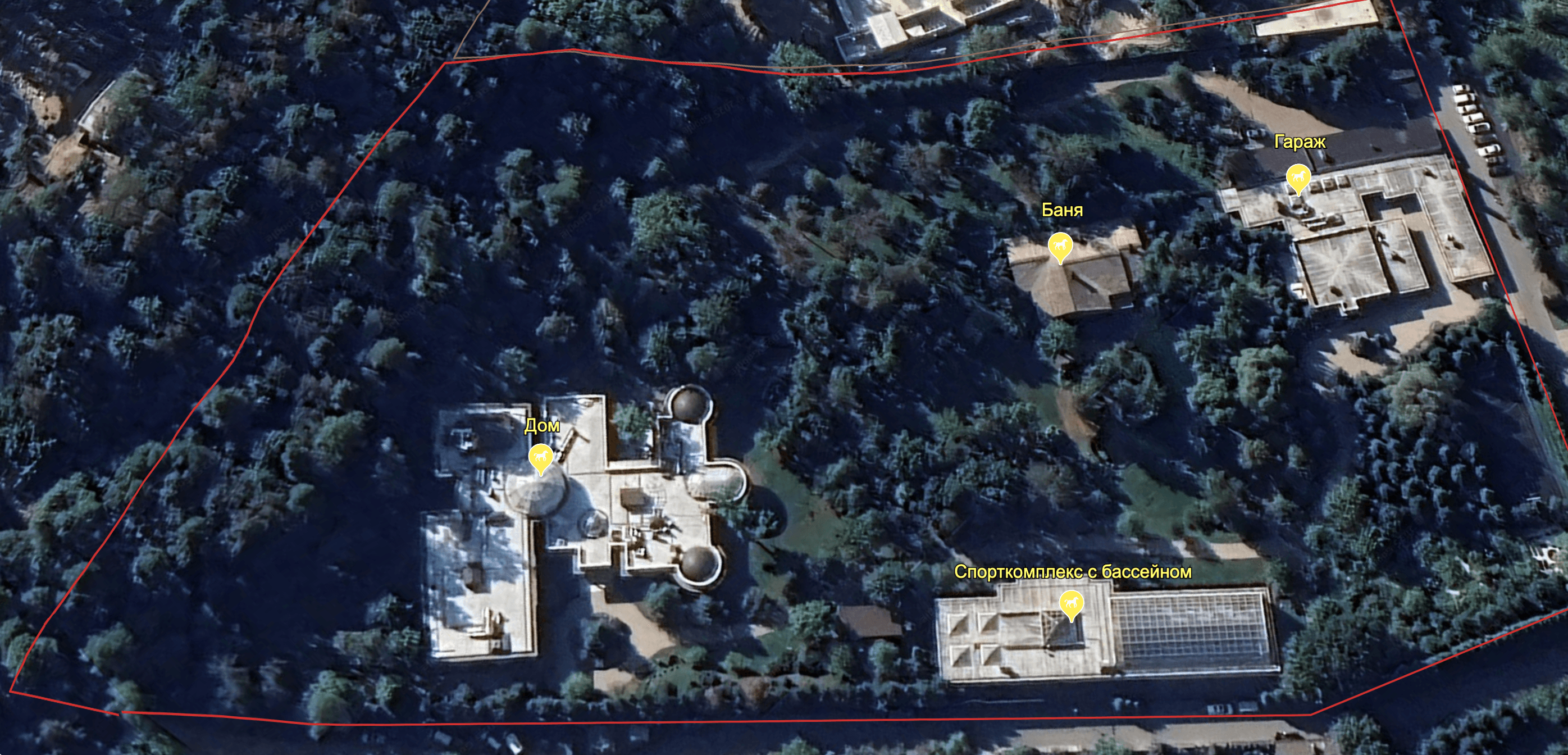

A two‑story house of 3,554 sq. m (larger than VTB head Andrei Kostin’s and TV host Nailya Asker‑Zade’s mansion in Razdory, valued at $240 million); a sports complex with a 1,500 sq. m pool; a bathhouse and a 1,000‑square‑meter garage. Builders who waterproofed the foundation pit back in 2013 posted photo reports: the pool is at least 25 meters long. All this stands on 26,695 sq. m (about 267 sotkas) of land—roughly comparable to Red Square. An entire estate in one of the country’s most expensive settlements went to Maria for half a million rubles (the amount is stated in the former owner’s 2022 financial statements).

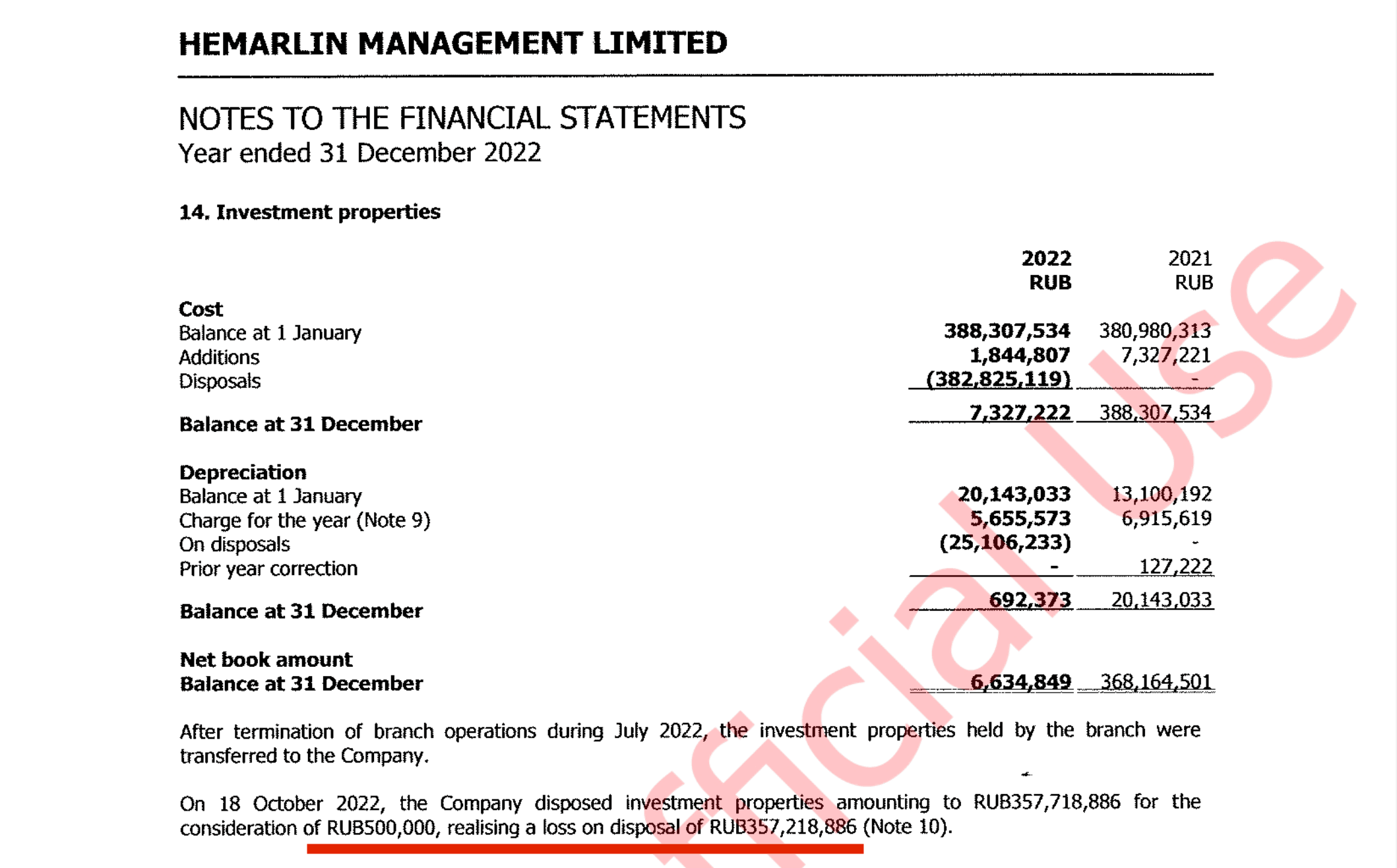

From annual report 2022 Hemarlin Management Limited.

The decision to dispose of the property, owned by the Cyprus company Hemarlin Management Limited (more on it below), was made at least by summer, several months after the war began: on July 25, 2022, the company’s Russian branch was closed. In its reports it explained this by the risk of “asset seizure by state authorities” as one of the potential consequences of the “conflict between Russia and Ukraine” and Russia’s “counter‑measures.”

The transfer was prepared in advance. A year before the deal, in October 2021, an unknown individual (name redacted by Rosreestr) began buying up parcels adjacent to the main plot. And two years before Klementieva formally became owner of Hemarlin’s real estate, she was already living at the Zhukovka dacha (country estate). In 2020, a COVID‑19 digital pass was issued to her phone number. “Purpose of trip”: “to the dacha,” with the address listed as the village of Zhukovka, 9A. That is the very dacha that, according to Rosreestr, did not yet belong to her.

In July 2022—four months before the official transfer of rights to the dacha near Novo‑Ogaryovo—two short calls were placed to her primary number. They came from the Zhukovka checkpoint (the NumBuster app recognizes the number as “Zhukovka Pass” and “Ilyinskoye Security”)—guards she had known since the time when lawyers in Nicosia were still preparing documents for the deal.

Maria Klementieva’s dacha on Novoogaryovskaya Street in DП “Ilyinskoye” (village of Zhukovka, Odintsovo district, Moscow region). Google Earth image.

Boundaries of land plots owned by Maria Klementyeva in the Ilyinskoye dacha settlement, village of Zhukovka (per cadastral register). Google Earth.

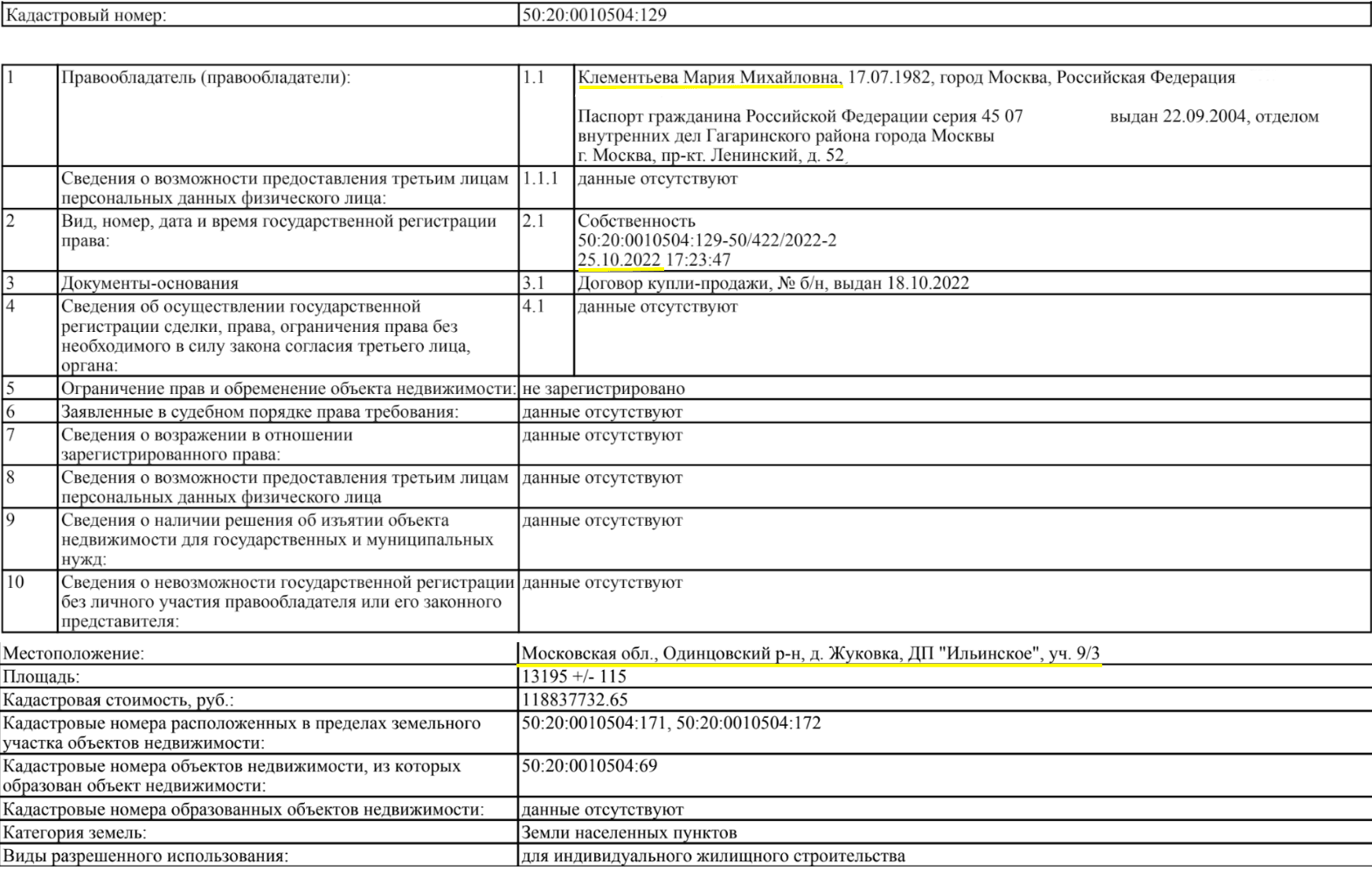

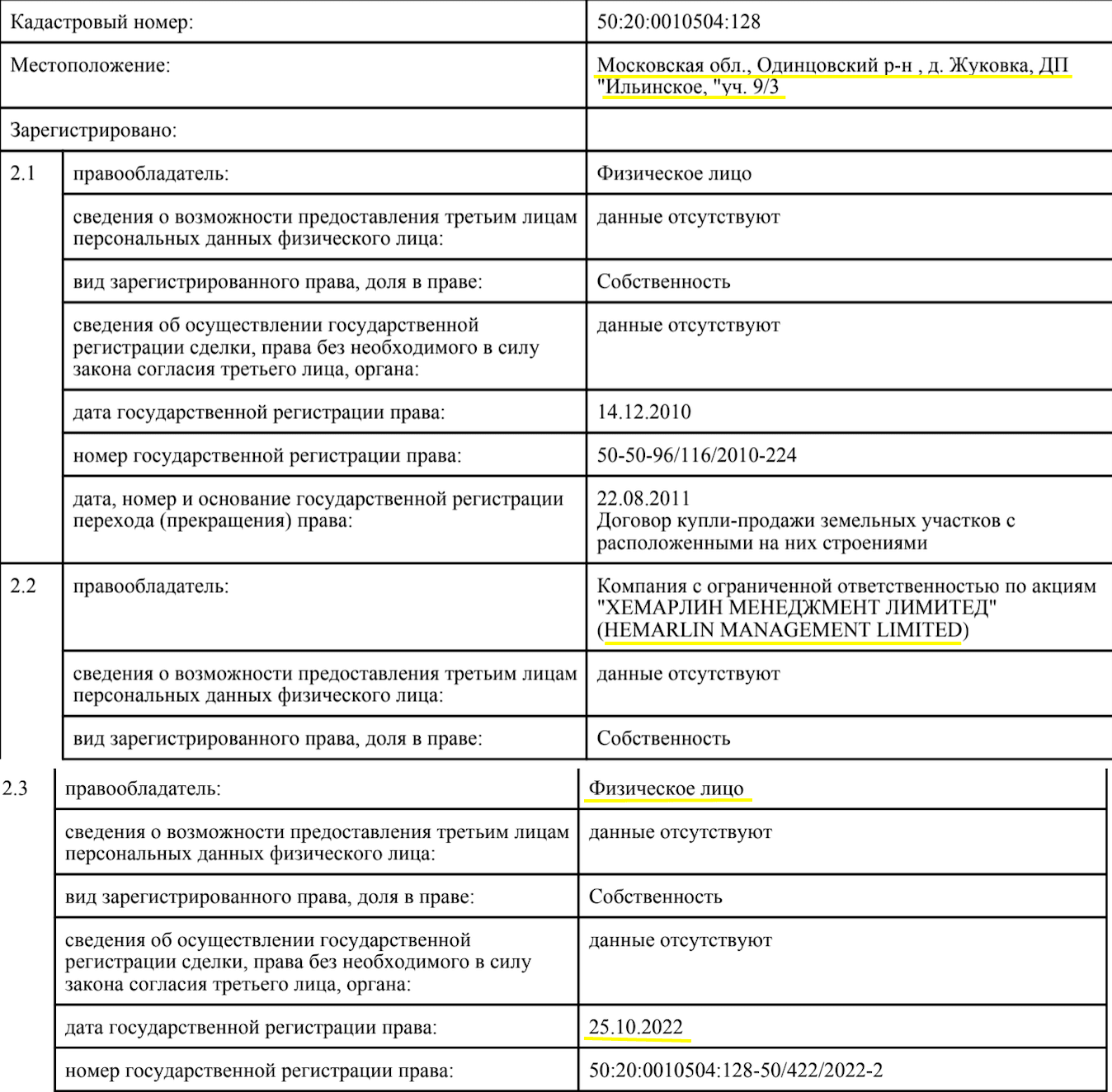

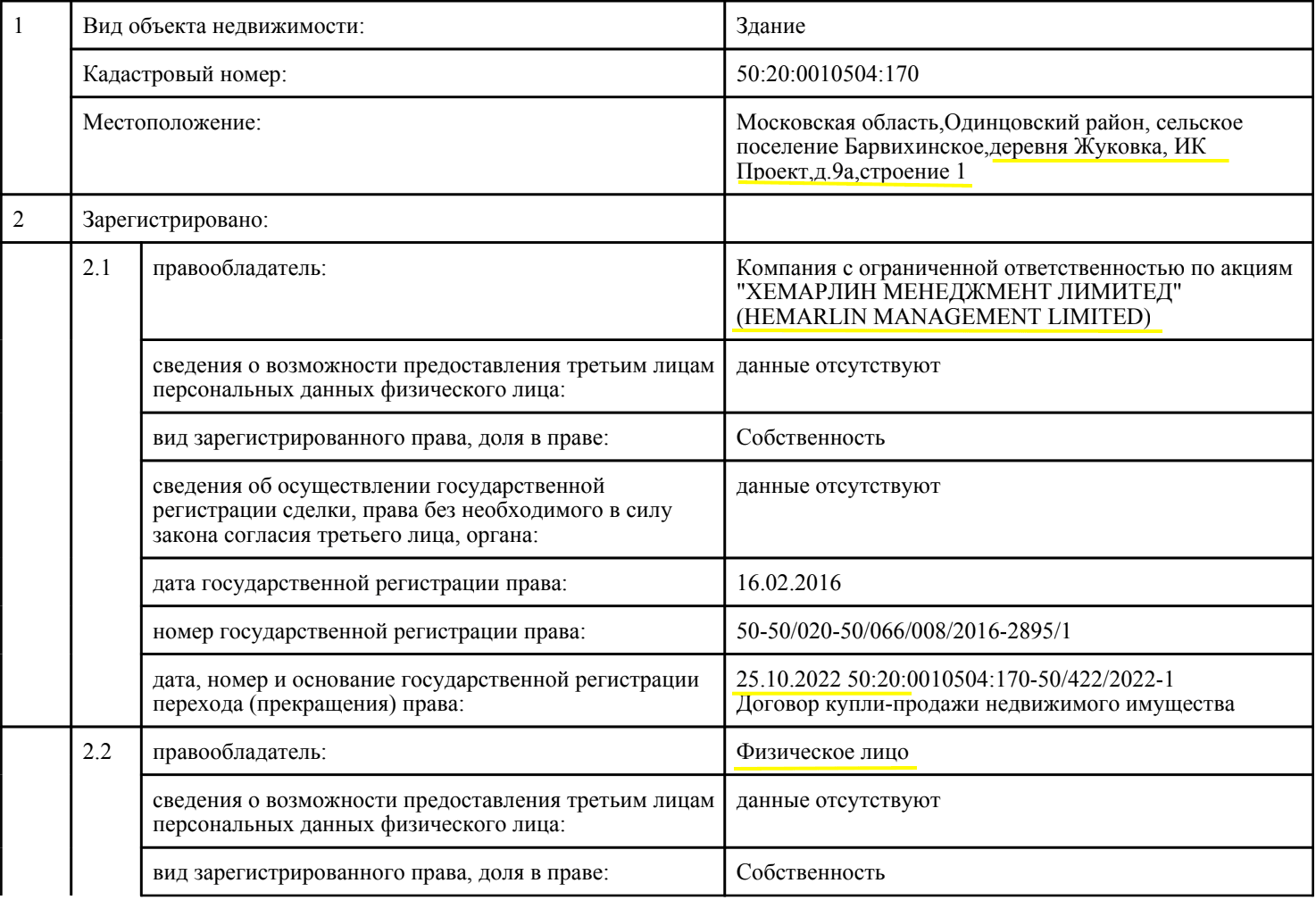

EGRN extract obtained by Explainer: transfer of ownership from Cyprus‑based Hemarlin Management Limited to Maria Klementyeva, 25 October 2022.

The same day, an adjacent plot also transferred from Hemarlin Management Limited to Maria Klementyeva. EGRN extract.

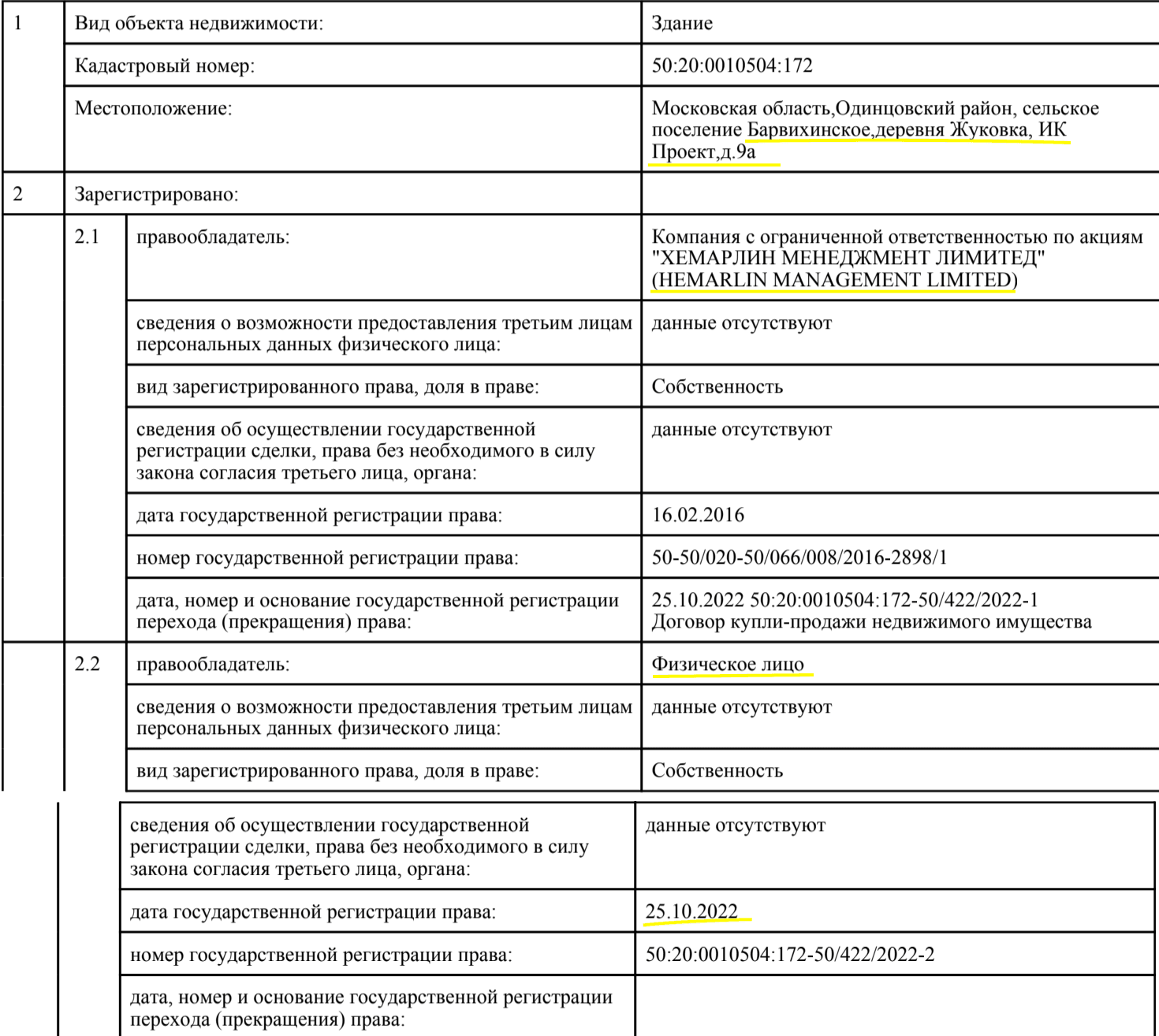

The same day, the house transferred from Hemarlin Management Limited to Maria Klementyeva. EGRN extract.

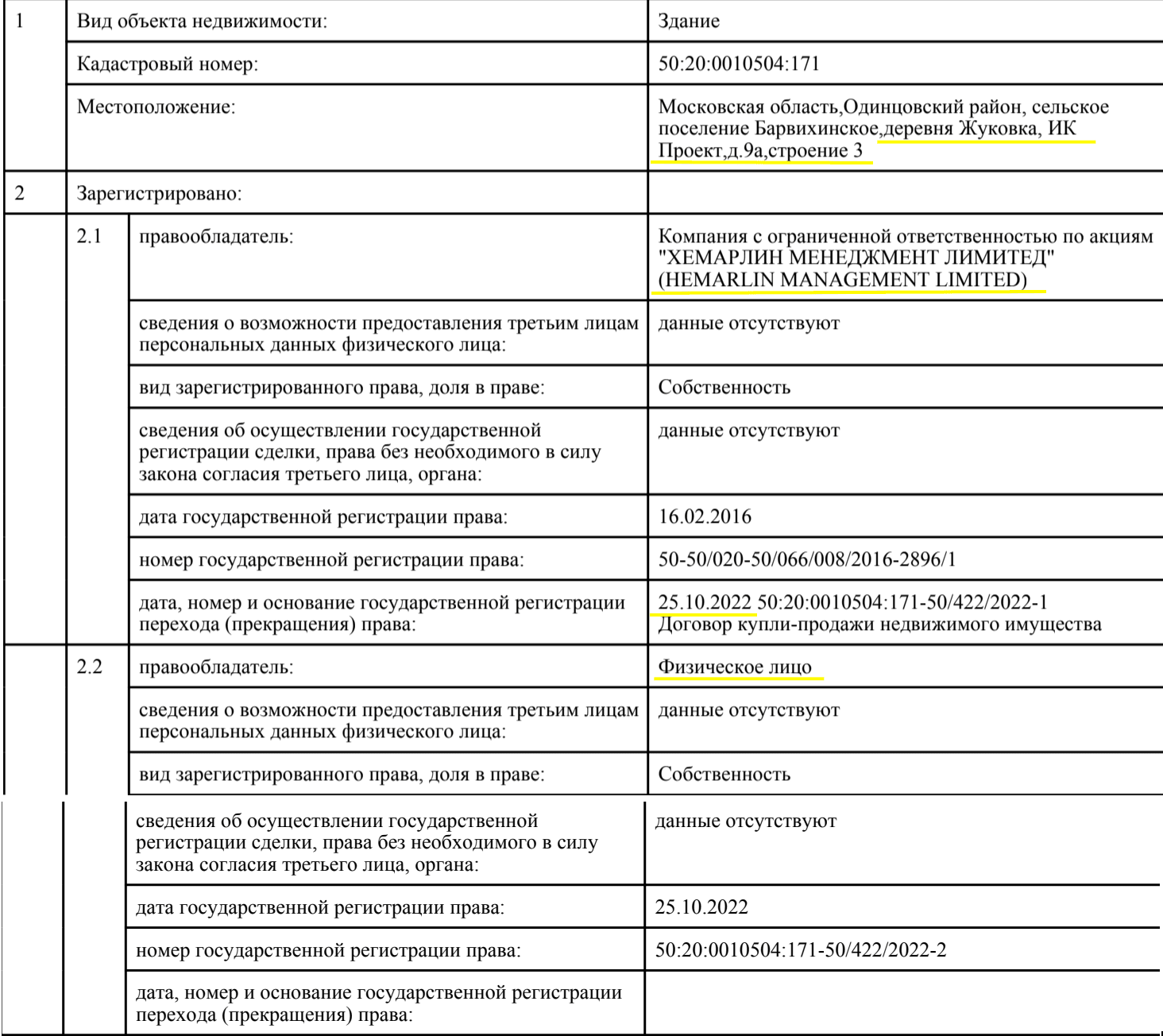

The same day, a sports complex with a pool transferred from Hemarlin Management Limited to Maria Klementyeva. EGRN extract.

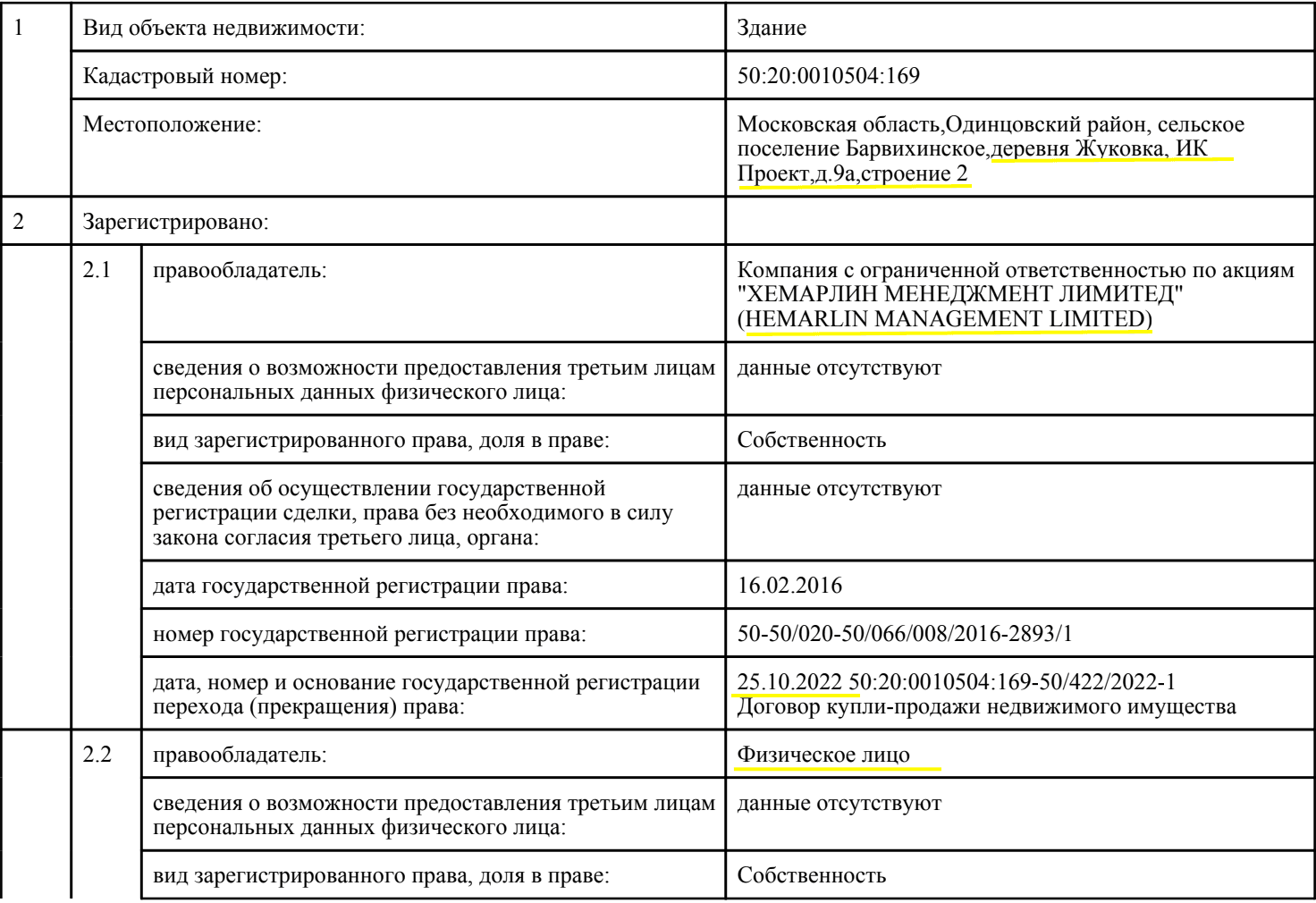

On 25 October 2022, a garage transferred from Hemarlin Management Limited to Maria Klementieva. EGRN extract.

On 25 October 2022, a bathhouse transferred from Hemarlin Management Limited to Maria Klementyeva. EGRN extract.

Klementieva found herself in unique company. The plot closest to her house (and closest to Putin’s residence) belongs to Olga Slutsker.

She received the estate seven years after a scandalous divorce from billionaire senator Vladimir Slutsker—in that dispute the Kremlin and Russian courts took Olga’s side, and her husband fled to Israel. In 2016, the land under her residence was gifted by a British Virgin Islands firm linked to Liechtenstein trusts used to hide assets of “Putin’s friends” Gennady Timchenko and Pyotr Kolbin. (i)

On the other side of Klementieva’s estate stretch 69,000 sq. m of Arkady and Boris Rotenberg’s holdings, with palaces photographed by Navalny’s team, reminiscent of a suburban Versailles.

Nearby is land registered to the son of murdered crime boss Vyacheslav “Yaponchik” Ivankov. EGRN updated rights to this plot in 2019; the property went to Kirill Fyodorov , a former Rostec executive.

Also in the vicinity are roughly two hundred sotkas (20,000 sq m ) of Elena Shebunova, former adviser to Sergei Shoigu, considered his secret partner and enriched via contracts with the Emergencies Ministry and Defense Ministry.

Another plot was seized in 2015 by Dmitry Medvedev (then prime minister) for the FSO (Federal Protective Service) special-protection zone; Rosreestr lists the purpose of this asset as “ensuring defense and security.” According to “Proekt,” a secret railway station was built there, four hundred meters from Putin’s residence, from which the president travels by personal armored train, as reported by the Dossier Center.

The center of gravity of this circle is Novo‑Ogaryovo, Vladimir Putin’s lifelong residence. A year and a half into the war, in September 2024, all these lands (including our protagonist’s dacha) were officially included in an FSO special‑protection zone, as seen on Zhukovka’s urban development plan.

Members of Putin’s family also live in the area. Adjacent lands, according to Proekt, began to be acquired by foreign companies from mid‑2006, linked to the Rotenberg network and Cyprus‑based Ermira Consultants Limited, which some investigators describe as the president’s “wallet.”

The story of her rise to the top of Russia’s elite is known only in her own telling. In her youth she spent six years in Paris, the athlete says in interviews (she grants them only to specialized equestrian media). Her version: she studied “public relations” at EFAP in Paris, interned at Cartier, worked at UNESCO, and speaks four languages. EFAP declined to confirm without Klementieva’s consent. Cartier and UNESCO did not respond.

In 2021, Maria Klementieva stated on Instagram she would not attend the European Championships in Hagen (7–12 September) because she returned to Moscow to care for her son sick with COVID. Her Instagram page is now closed; the statement is cited via her profile on Prokoni.ru.

Klementieva restricts access to information about herself. Her Instagram is private, though for the first two years it served as a source of news about her sporting career. The page was created in 2019, coinciding with her Grand Prix debut in Nice. On Facebook, where she has been largely inactive since 2022, there are only photos of horses and competition results. In February 2024 she updated her profile photo—to an image of a horse’s nostrils. No photos of the “husband” mentioned in interviews appear on social media.

Maria was born in 1982 and has been registered since the late 1990s in an 80‑square‑meter municipal apartment in Moscow on prestigious Leninsky Prospekt, building 52. The same address was indicated by Maria as the sole beneficial owner of Relmond Holdings Limited in the British Virgin Islands, which she owned until its closure in 2021. This information appears in the ICIJ Pandora Papers. But the apartment is not her property: it is municipal housing under a social‑rent contract. This means Moscow’s government, for some reason, deems the Klementiev family low‑income.

Klementieva does not pay utility bills. The state housing provider “Zhilishchnik” filed suit in March 2022, stating the apartment is city property provided under a social‑rent contract. The claim lists other registered residents besides Maria: her mother Irina Maslova, her older brother, and likely Klementieva’s niece.

From 2005 to 2018 the Russian tax service did not receive income declarations from Klementi

eva (from age 23 to 35)—according to a Gold Mustang interview, during that time she was supposed to have been studying PR in Paris, and from 2010 was raising children.

Her first regular income appeared at age 37. Over four years (2019, 2020, 2022, and 2023) Klementieva declared at least 16.5 million rubles. She received regular salaries from two companies within the structure of Transmashholding co‑owners—OOO Tekhkom (about 138,000 rubles monthly) and JSC Group Avtolain (40–50,000 rubles monthly). Tax returns do not specify her position or job duties. Over half of that sum—8.4 million rubles—arrived as a one‑time payment in 2019, classified as “other income” from a source not stated in the declaration, more than five times her annual salary. In 2022, prize payments from Moscow’s Sports Department totaled 180,000 rubles, after her victory at the Moscow championship at the New Century equestrian club where she trained.

The athlete mentions in interviews that she has a husband—she does not disclose his name. The mother of three has never been married in Russia, according to civil registry data.

Despite no official income, vehicles totaling 68 million rubles ($855,000) were registered to Klementieva. In 2010, when her eldest son Gleb was born, a Porsche Panamera ($135,000) was registered in her name.

In 2012, when daughter Vasilisa was born, an Aston Martin Virage Volante ($226,000) was registered. A rare British convertible produced for only two years. In 2014, a third child—a son, Bogdan—was born, after which she took up an expensive new hobby—horses.

In 2018 and 2020—the start of her equestrian career—two Bentleys were added to her fleet (Bentayga and Continental GT, from $400,000 each). The latest acquisition in 2020 was a McLaren 720S Spider ($287–330,000)—a different league entirely. That year the athlete won her first cup in Russia; she also registered her first supercar.

Her children study at the British Repton Al Barsha school in Dubai, where upper‑school tuition costs about 22–23 thousand euros per year. According to Maria’s remarks in Eurodressage, they speak several languages—Chinese, English, French, Spanish—and are learning Arabic. By January 2025 the family was living in Dubai, as evidenced by a post on the school’s Instagram. Dubai winters, Klementieva says, are “excellent for study and development.”

Maria Klementieva’s three children bear the surname Komissarov and patronymic Dmitrievich. However, for the daughter, Vasilisa, the “father” field is blank. The boys’ father—and possibly the girl’s—is the 55‑year‑old billionaire Dmitry Komissarov, chairman of the board and co‑owner of Transmashholding (TMH) with dollar billionaires Andrey Bokarev and Iskandar Makhmudov. TMH is a perennial leader of Forbes’ “Kings of Government Contracts” rankings.

Komissarov, like Klementieva, avoids publicity and does not use social media. According to Federal Tax Service data available to the editors, his official income for 2019–2023 totaled about 13.1 billion rubles. Most of this came from dividends from structures linked to TMH. But in 2023–2024 his earnings structure changed radically: instead of billion‑rubles dividends, he began receiving “material assistance” and interest on bank deposits. By 2024 his declared income had fallen about sixtyfold compared to peak levels in 2019–2020. (i)

Transmashholding Chairman Dmitry Komissarov (left) and First Deputy Minister of Natural Resources and Environment of Russia Konstantin Tsyganov at a strategic meeting on import substitution of industrial software at the Government Coordination Centre. September 2022.

A Kommersant fact sheet from 2008 mentioned “a wife and two children” of Dmitry. This referred to Marina Kiseleva, who took her husband’s surname. Their marriage was dissolved on June 19, 2010, and exactly a week later, on June 26, Komissarov’s first son with Maria Klementieva was born (she was 28 at the time).

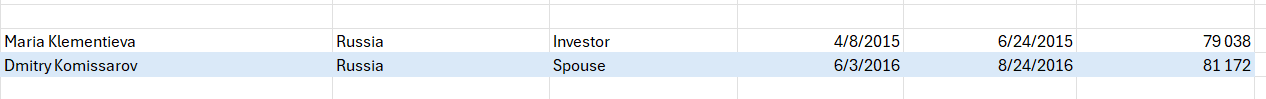

Five years later, Klementieva and Komissarov obtained Cyprus “golden passports” as a family. Klementieva was the investor: Cyprus Papers documents state she applied for citizenship in April 2015 under the program requiring at least €2 million in investments. Komissarov applied a year later, in June 2016; citizenship was approved by late summer. Since family visas require an official marriage, the circumstances of approving applications a year apart remain unclear.

In Cyprus, the couple acquired a villa in the Pantheo Luxury Residences complex in Limassol—a three‑bedroom home with a pool, a hundred meters from the beach. Explainer found this address in the French commercial register: Klementieva and Komissarov listed it as their permanent residence when registering the French château (the circumstances of which will be covered in a separate chapter).

In Russia, they lead conspicuously separate lives: different surnames, different registrations. Their houses in Zhukovka are on the same street, but they are different homes. Phone billing analysis revealed only one call between them in November 2020 (under a minute). In other people’s phonebooks Klementieva appears under her own name, and only one entry from 2018 lists her as “Masha Komissarova.”

In digital services (food delivery, marketplaces) Maria Klementieva and Dmitry Komissarov use personal phones and emails, but delivery addresses never overlap. (i)

Klementieva has been registered since childhood on Leninsky Prospekt. In forms, Komissarov lists a home on Novo‑Ogaryovo Street—the same street where Klementieva’s dacha is located, next to the president’s residence and Rotenberg family plots. No public photos of the pair exist. Explainer’s sources in TMH’s orbit, equestrian sport, and Rublyovka (Moscow's elite suburb) residents did not confirm familiarity with such a couple. A source close to the leadership of a state corporation had heard of Klementieva as a figure of “society,” but did not know of her connection to TMH’s co‑owner.

The only place where their connection is documented is TMH’s pass system. In 2021, a corporate pass for Maria Klementieva was issued by JSC TMH.

Dressurzentrum Máriakálnok.

Before the war, they flew abroad together nearly two hundred times. Main destinations—France: Nice (32 departures), Chambéry (10), Clermont‑Ferrand (12), Paris (11). They also flew to Germany (Friedrichshafen, Munich, Bremen). Friedrichshafen is the headquarters of Rolls‑Royce Power Systems AG, a key TMH partner.

In a 2021 interview Klementieva said she loved flying away for weekend hikes with an unnamed husband. But if going abroad didn’t work out, “we can even take a walk around the Moscow region,” she told Gold Mustang magazine. She claimed to be happy in her private life; her favorite pastime is “holding hands… enjoying a good dinner with a glass of wine.”

On February 19, 2022, the pair flew to Friedrichshafen, Germany. They returned after the invasion began, on February 26. This was their last trip to Europe in our border‑crossing databases covering flights from 2014 through late 2023.

After the war began, European routes disappeared, and main destinations shifted to the UAE (Dubai, Jebel Ali) and Turkey (Bodrum, Milas, Istanbul).

The planes they used are noteworthy:

Bombardier Global 5000 (RA‑73545), linked to Boris Rotenberg. During Prigozhin’s mutiny on June 24, 2023, Klementieva and Komissarov flew this aircraft to Azerbaijan. That same day, Klementieva’s neighbor in Zhukovka, Arkady Rotenberg, also left the country. The pair returned on June 26 on a Challenger 850 (three‑hour charter cost—5.7 million rubles).

Bombardier Challenger 850 (RA‑67244) — an aircraft used by fugitive Ukrainian businessman Sergei Kurchenko, “Yanukovych’s wallet.”

Gulfstream G650 (OE‑IIH) — the personal jet of billionaire Iskandar Makhmudov. In March 2016 Komissarov flew on his partner’s aircraft to Zurich.

Gulfstream G600 (OE‑IPL) — their primary transport from April 2021 to February 2022. Registered in Austria.

Klementieva flew to competitions without Komissarov: perhaps he had no time to support the mother of his children from the stands. He has many state affairs: he attends meetings with Putin and Mishustin, proposes bond issues worth hundreds of billions to the president, and oversees federal IT projects for 8.3 billion rubles in state grants. For the state, he is a key contractor and expert. For Klementieva—he is not quite a husband, whose name she prefers not to reveal.

Château de Pée does not appear on tourist lists of “must‑see castles” or guides to Cher. It is a fully private estate in a tiny village. The French register records that since 2017 Maria Klementieva has managed the company that owns Château de Pée in the department of Cher.

Château de Pée is an old country manor in the commune of Neuvy‑le‑Barrois, about 230 km south of Paris; exact data on its construction date and first owners are not publicly available. Neuvy‑le‑Barrois is a sparsely populated rural commune, surrounded by fields and forests; nearby cities like Bourges and Nevers are dozens of kilometers away.

Klementieva’s rights to the asset appeared in 2017. In 1987, attorney Patrice Gassenbach purchased the estate with roughly 45 hectares of land and registered it under a special civil company to optimize taxes. Thirty years later the scheme became more complex: control over the château passed to a Monaco structure—a jurisdiction long famed for high secrecy around beneficiaries, which only after 2018 began formally introducing a beneficial‑ownership register that is not publicly accessible.

In November 2017 two new participants entered the capital of the French company owning the château—Klementieva and Komissarov, listing their Cyprus address. Nearly all shares of Château de Pée were transferred to a Monaco company, and Klementieva and Komissarov each received one symbolic share. The nominal price—€928.89 per share; overall valuation in documents—about €930,000, i.e., at least half the market value; sufficient for French tax registration, but not reflecting the real transaction price.

Before the Klementieva‑Komissarov tandem appeared in the register, Ekaterina Sotnikova had been listed for two years—a Latvian‑born owner of the Paris watch boutique Ekso Watches Gallery. A 2013 Europastar article quotes her saying she was an elite gymnast in her teens, suffered an injury and left the sport; later friends in Russia “closely connected with the political family of President Putin” introduced her to France’s UMP party, where she handled relations with elected officials “in the East” and met her future husband, who gifted her the watch…boutique in Paris.

In 2016, Sotnikova’s name disappears from the documents as abruptly as it appeared, giving way to the Monaco structure. In August 2025 Komissarov exits: he sells his single share to Klementieva for €928.89, after which Klementieva transfers it to her mother, Irina. As a result, nearly 100% of the company owning the château remains with the anonymous Monaco entity. Klementieva is listed as gérant (manager) in the key structures through which the house, lands, and operations are held. A separate agricultural company, SCEA DE PEY, registered at Château de Pée, owns and operates the surrounding acres, specializing in horse breeding and livery services; in it, Klementieva holds 99% of the shares, and her mother, Irina Maslova, holds the remaining 1%. Thus, the château itself is legally concealed behind Monaco, while Klementieva and Maslova manage everything in and around it.

Neither in childhood nor youth did Maria engage in riding, and she appears to have done no preparation for a sporting career—unlike most of her current competitors.

Maria entered equestrian sport only at age 32, after taking her daughter to lessons in 2014 and experiencing a “moment of illumination,” she said. Her training base at once became one of the most closed and prestigious clubs—KSK “Novy Vek” (New Century) on Rublyovka, six kilometers from Novo‑Ogaryovo.

The club belongs to the family of former district prosecutor Anatoly Merkulov and his wife, Inessa. In the 1990s Merkulov left service to head the Moscow mayor’s enterprise “Zhilkooperatsiya”—that was when the equestrian club emerged. Inessa Merkulova runs the establishment, and the ex‑prosecutor holds an honorary president role, found Scanner Project.

A club regular was Anna, daughter of the powerful judge Olga Egorova, who led the Moscow City Court for 20 years—Anna celebrated her wedding there.

Daughters of Investigative Committee head Alexander Bastrykin trained there. The vet clinic served Putin’s dogs, Kadyrov’s horses, and Medvedev’s cat and three horses.

Putin himself visited: on November 11, 2011, the club hosted a meeting of the Valdai Club with the country’s leader, then serving as prime minister. The gathering took place at the restaurant Le Cheval Blanc on club grounds. In 2016, the restaurant passed to Merkulov from “Putin’s chef” Yevgeny Prigozhin, according to business‑registry records.

The first competition horse (Anilin) for the novice rider Klementieva was provided by the club’s owner, Inessa Merkulova—the FEI database retains the ownership data. By 2018 Klementieva had at least three horses. She purchased the American Hanoverian stallion Doctor Wendell MF in winter 2016 for €1.1 million, as recounted ↗ by its breeder, Marianne Haymon. Exact prices for the other two were not disclosed. Who funded the stable’s creation and upkeep is unknown; Klementieva’s official story of “parental help” does not withstand scrutiny—the family has no business of comparable scale.

Seven years after beginning, at the national championship Klementieva (age 37) outscored the 57‑year‑old Olympian Merkulova and became Russian champion, winning the Grand Prix freestyle in dressage.

That same year, however, she was dropped from the national team ahead of Tokyo 2021 due to her horse’s injury. But Klementieva was undeterred and, six months before the war, insisted: “Now we’ll aim for Paris. It’s almost home to me—I lived there six years!”

War and FEI then upset her plans: the federation banned Russians from FEI tournaments. Klementieva remained in Russia and stopped giving interviews. In autumn 2022 she became Putin’s neighbor.

As Klementieva triumphed in the arena, entries grew in the tax database. In 2019 she founded two companies—“Equestrian Club ‘Porechye’” and “Rennen.” Stated purpose: horse breeding.

The real result—chronic losses. Companies that formally own assets worth nearly 200 million rubles report revenues at a street‑stall level: about 166,000 rubles per year. Porechye’s capital hole is minus 43 million: the firm owes more than it owns.

The director of this “horse business” is Andrey Borisov—a former lawyer for Transmashholding, as he wrote on social media.

Rennen had one truly valuable asset—almost two hectares near Zvenigorod, on the Moscow River. The plot has protected status: the ancient settlement “Dunino‑11” and part of the Popov estate, an archeological heritage site. Any work requires separate approval.

But doors open easily for TMH people. In 2024, without permits, construction began on burial mounds: inspectors from the regional cultural‑heritage directorate recorded an illegal road on the plot. By then, the land had already left Klementieva’s ownership—she sold it to Konkur, fully owned by the father of her children, Dmitry Komissarov. In January 2024, Rennen’s charter capital jumped from 10,000 rubles to 87 million with 442,000 rubles in revenue that year and zero for all other periods.

The scheme looks like this: the wife buys a protected site, holds it in her name while the husband prepares a project, and then transfers it for development. An eternal servitude is imposed on the plot in favor of road giant DSK “Avtoban,” linked to major infrastructure projects and partners of Arkady Rotenberg. Builders can now use the land regardless of who is owner. Under the “equestrian club” banner, a reserve was effectively captured for the needs of road barons.

That same fortunate 2024, 28 million rubles appear in Maria’s personal accounts (it was 1 million in 2022). Although official work in two companies in the Transmashholding group brought her about 2 million that year. Since 2022, funds on her personal accounts rose from 1.2 million to 27.8 million rubles. In 2024 alone, interest on deposits earned her 4 million rubles—twice her official employment income (~2.1 million rubles).

But Klementieva’s main assets today are her houses and acreage. By our estimates, their total market value is 9 billion rubles (about €100 million). (i)

Now back to the firm that delivered billions in property to Klementieva. (i)

Hemarlin is a Cyprus nominee company, created in 2011 specifically to own and manage investment real estate in Russia—its charter says so explicitly. It did so for almost 13 years, from 2011. Through a branch with an address in the Odintsovsky district of the Moscow region, Hemarlin regularly paid utility bills and land tax—the electricity bill for the first half of 2022 was 7 million rubles, and the property tax was 5.4 million rubles.

The real estate was purchased for $6 million in August 2011. Novo‑Ogaryovo was then a prime‑ministerial, not presidential, residence; only at month’s end did Putin announce his return to the Kremlin and Medvedev’s return to the government.

Rosreestr extracts confirm the purchase—country land on Novo‑Ogaryovo Street in the “Ilyinskoye” dacha settlement in the village of Zhukovka. It was Hemarlin’s first and only land investment. Of the $6 million spent: $5,605,000 went to land; • $395,000—to buildings.

The seller was a multimillionaire linked to port‑fuel business in the Baltic states, Sergei Pasters. (i)

The $6 million purchase was fully paid by an interest‑free loan from parent Zamora Corporation Limited (British Virgin Islands), says Hemarlin’s 2011 report. Zamora owned 100% of Hemarlin from September 2011 to December 2014. The Panama Papers link Zamora to Boris Mints—co‑owner of Otkritie Bank, a longtime associate of Chubais in the State Property Committee and the Union of Right Forces.

At end‑2014, control over Hemarlin passed to Palser Foundation (Liechtenstein)—a structure shielding the ultimate beneficiaries of the estate. The new owner immediately began large‑scale construction. New facilities rose on the plot in 2015–2016.

Cyprus documents put construction costs at 50.3 million rubles.

Over seven years (to 2021) the company received 357 million rubles in loans from related parties: most funds covered operating costs and old debts. By sale time in 2022, the asset’s book value was 357.7 million rubles. Selling it to Klementieva for 500,000 rubles (0.07% of cadastral value) the company recorded a loss of 357.2 million rubles.

The same day lenders wrote off Hemarlin’s debts. In 2022 new loans from structures affiliated with Palser Foundation’s controlling shareholder were forgiven.

A fragment of Hemarlin’s report records the sale of Rublyovka assets for 0.14% of book value.

In the accounts this was carried as “other income,” offsetting nearly the entire loss from the sale and allowing no tax on the transaction since it was unprofitable. In essence, shareholders swapped the real estate for forgiving their own debts. The creditors (Investcom Limited, Daclipo Management, Kiseritano Development), like landholder Hemarlin, were controlled by Palser Foundation.

In sum, the scheme looks like:

Related structures lend Hemarlin 357 million rubles; about 50.3 million goes to palace construction.

Facing risk of asset seizure from a Cyprus company in Zhukovka, shareholders transfer it to Klementieva for a symbolic 500,000 rubles, booking a giant loss.

Creditors forgive debt to their related company.

The company is liquidated.

In July 2023 Cyprus’s official gazette published a notice of Hemarlin’s liquidation. Barely two weeks had passed since the EU’s 8th sanctions package (October 6, 2022), which made maintaining such structures impossible—the ban on legal services, combined with the earlier trust‑services embargo.

Hemarlin’s offshore anonymity was broken by a single document. In December 2014, for just twelve days, Hemarlin’s sole shareholder is Dmitry Komissarov—by then already the father of Maria Klementieva’s children. In registration forms he listed a Moscow address on 7‑ya Parkovaya Street—a modest area for a multimillionaire in Shchyolkovo, eastern Moscow. Yet Komissarov at the time sat on the Russian Railways (RZD) board and represented TMH’s interests there.

The aforementioned Boris Mints and Dmitry Komissarov together built Russia’s largest private pension business—NPF Blagosostoyanie OPS . The board included Mints and his son Dmitry, the RZD representative Dmitry Komissarov, and former finance minister Alexei Kudrin as chairman.

Two years later, the name of another hidden Hemarlin operator surfaced—thanks to a fight on the Volga’s shore in May 2016.

United Russia MP Alexander Sedyakin wrote a VK post, “we were vacationing in Tver region on the Volga’s bank. Thugs attacked us out of hooligan motives.” The MP’s version was debunked by Life: the conflict began when Tver businessman Sergei Rebotenko demanded they leave—the MP was on private land, felling forest. The matter escalated to a brawl and a police call.

Checks showed: Rebotenko is director of Hemarlin Management Limited’s Russian office. His career is tightly tied to TMH structures. In 2023, the Moscow group “Key Systems and Components,” part of TMH, began buying shares of St. Petersburg’s Elektropult plant; Rebotenko was appointed CEO. Like Klementieva, Rebotenko also competes in dressage, riding for elite club “Otrada.”

Another link: Roman Klementiev —Maria’s brother—is CEO of OOO “MPK”. MPK’s beneficiaries are the same: Komissarov (21.9%), Bokarev (20%), and Makhmudov (19.8%). Through this company they control Moscow’s suburban rail (CPPK).

Transmashholding has an intermediate parent in Cyprus—Breedior Investments Limited—through which CEO Kirill Lipa and board chair Dmitry Komissarov exercised operational and voting control over JSC Transmashholding.

Reports show Hemarlin (Zhukovka land) and Breedior (TMH) shared the same funding “wallet”—Investcom. Money moved among structures as “related‑party loans,” sometimes at near‑zero interest. Hemarlin and TMH’s Cyprus vehicle also shared auditors—InterTaxAudit. (i)

Links to Rotenbergs and Kremlin structures

Cyprus law firm Kinanis LLC prepared Hemarlin’s incorporation documents in 2011. According to Cyprus registries, the firm managed European real estate and served as its formal owner, including the Rotenberg brothers’ villa in Spain. (i)

At the same time, Kinanis provided services to Ermira Consultants—a structure that financed construction of the Gelendzhik residence, later identified by journalists as linked to the president’s entourage.

Since 2011 Hemarlin’s legal support was handled by Christodoulos G. Vassiliades & Co LLC. It executed key company transactions, including transferring control from Komissarov’s structure to Liechtenstein’s Palser in 2014.

In The Kremlin Playbook in Europe (2020), the Center for the Study of Democracy identified Vassiliades & Co as having “the closest ties to the Kremlin” among Cyprus law firms. Its clients included oligarchs Alisher Usmanov and Roman Abramovich. The firm also provided corporate services to Sberbank’s Cyprus subsidiaries.

In 2023 the U.S. and UK sanctioned a Vassiliades & Co director for aiding Russian oligarchs in hiding assets. In Russia, he was charged over laundering €1 billion stolen from Promsvyazbank depositors.

Audit cover

InterTaxAudit, which certified Hemarlin’s accounts, was presented in correspondence as an “affiliated partner” of Vassiliades & Co. One of its managing partners—Egli Tamani Fella—personally signed Hemarlin’s 2012 and 2015 reports.

In 2023 the U.S. Treasury sanctioned Fella, noting her role in hiding VTB’s assets and those of its clients in the UAE and Oman to evade sanctions.

The same audit firm worked with RAIF funds—investment structures that, until 2022, did not disclose ultimate beneficiaries in public registries. These funds were used to hold yachts and real estate of Russian clients. RAIF funds were managed by Inveqo Fund Management, owned by the spouse of Vassiliades & Co’s director. (i)

In 2024 the Zhukovka landowner returned to top‑level sport—but now under Cyprus’s flag. Maria Klementieva avoided FEI’s requirement to sign a neutrality declaration renouncing support for the war: instead of the procedure required for Russian athletes, she presented an EU passport obtained via the “golden” citizenship‑by‑investment program.

Maria Klementyeva at her daughter’s performances. Hungary, 2024.

In July 2024 Eurodressage quoted the new Cypriot: “Cyprus has always been home for me, I live between two countries.” Meanwhile, Russian border databases do not record frequent trips by Klementieva and her spouse to Cyprus—only a few visits by Komissarov in 2016–2017. Her daughter, Vasilisa Komissarova, also began competing for Cyprus’s federation.

A flag change requires a stable change. In 2024 Klementieva acquired the Danish gelding Gammelenggårds Zappa; its previous owner was Swiss company K Spirit AG of Peter Studer. In 2021 his name appeared on the list of TMH‑affiliated persons.

The second horse, Champagnier, which competed for Klementieva in Russia in 2019–2021, was already starting at international events by September 2024. Given veterinary‑quarantine timing, this indicates the export of the asset began long before the public change of citizenship.

Over two years (2024–2025), under Cyprus’s flag, Klementieva appeared at seven tournaments (19 starts) in five countries (from Qatar to France). Her average result—67.1%—barely meets the FEI qualifying minimum; prize money for such performances does not exceed a few hundred euros per start. (i)

“When huge money is spent on you, but you perform worse than everyone in Europe, it means the result is not needed. They're not paying for that”—journalist Sergei Aslanyan, an equestrian enthusiast familiar with the sport’s elite, believes.

“What does a person feel who becomes national champion for the first time?—Incredible pride for the horse,” Klementieva answerednin 2021’s GoldMustang.

On English‑language Facebook, however, the tone is different: users recall a scandal at Norway’s 2020 Lillestrøm tournament. Stewards caught her groom beating the horse Champagnier with a whip in its stall. Klementieva, as responsible party, was immediately disqualified.

Maria Klementyeva (right). Cyprus, 2024. CYEF—Cyprus Equestrian Federation.

No one in Russia ever asked her about the disqualification; for Western audiences she is willing to explain. “I would like to clarify this situation, as this is a horrible experience for me… This groom is not my permanent groom…”—the rider personally commented on the Facebook post with the news.

Klementieva describes herself as “hyper‑responsible,” ready to “break through walls and work to exhaustion,” training for hours in the arena. But some dressage professionals believe she bought success.

Such comments were left by riders of different levels from different countries under Eurodressage’s “Six years in the saddle, focus on Paris‑2024” post, which recounts how she went from zero to Olympic level in six years. Klementieva admits in the text that between herself and professionals there is a gulf of experience. How she compensates (per the article): rides 4–5 horses daily at different training levels; reads books; takes master classes; her main goal is “to reduce the gap” between amateurs and pros as quickly as possible through volume of work.

“I don’t understand what’s special here… just another millionaire buying a ticket to the Olympics. … Try to do it! With money or without! And in Russia you also have to beat an entrenched establishment holding the reins of national‑team selection.” — Eleonora Kinsky, Czech Republic (CDI Grand Prix).

“Hm, just watched her recent video from Poland. Very rough (not subtle), tight riding plus the ‘groom incident’ doesn’t bode well at first glance. Yes, Grand Prix is incredibly hard, but a great horse helps immensely, and there’s a huge difference: do I train the horse up myself or do I ‘just’ ride a perfectly schooled horse at that level.” — Tina Ohler, Switzerland. Riding instructor, stable owner.

“What amateur rider wouldn’t dream of riding 6 top‑level horses a day, having access to top trainers, and heaps of time for self‑education! … Money certainly helps. Articles like this are a slap in the face to all the amateur riders juggling full‑time jobs, family, and riding, who have to work unbelievably hard…” — Katja Fuerstenberg Gwin, USA (Texas, Dallas). Successful amateur rider, ~70% results at smaller shows.

“This may sound like envy, but for those of us grinding from absolute zero without financial backing, it’s hard to hear so much praise for someone who simply decided to get to the top by buying six Grand Prix horses…” — Sian Eve Parkes, UK. Dressage rider competing at national level (British Dressage).

Klementieva’s profile is tailored to a European readership; it has never been published in Russian. The piece, quoting the athlete, claims Klementieva “grew up among horses.” In reality, she grew up on Leninsky Prospekt, Moscow.

While Klementieva was mastering European arenas, her asset at Novo‑Ogaryovo changed status. On July 15, 2024, uniform encumbrances were registered on four objects: the residential. Explainer sent detailed questions to Maria Klementyeva and Dmitry Komissarov, but they had not responded by the time of publication.